Tyler ‘Bynine’ McMaster, indie artist and game developer, tells Vince Pavey all about the work that went into making his retro platformer dreams into a reality

Indie games have paid tribute to classic video game adventures for a long time, although outside of a growing fondness for the boomer shooter, they have largely seemed happy and comfortable to do so with a comfortable reverence for the 8-bit and 16-bit eras of software.

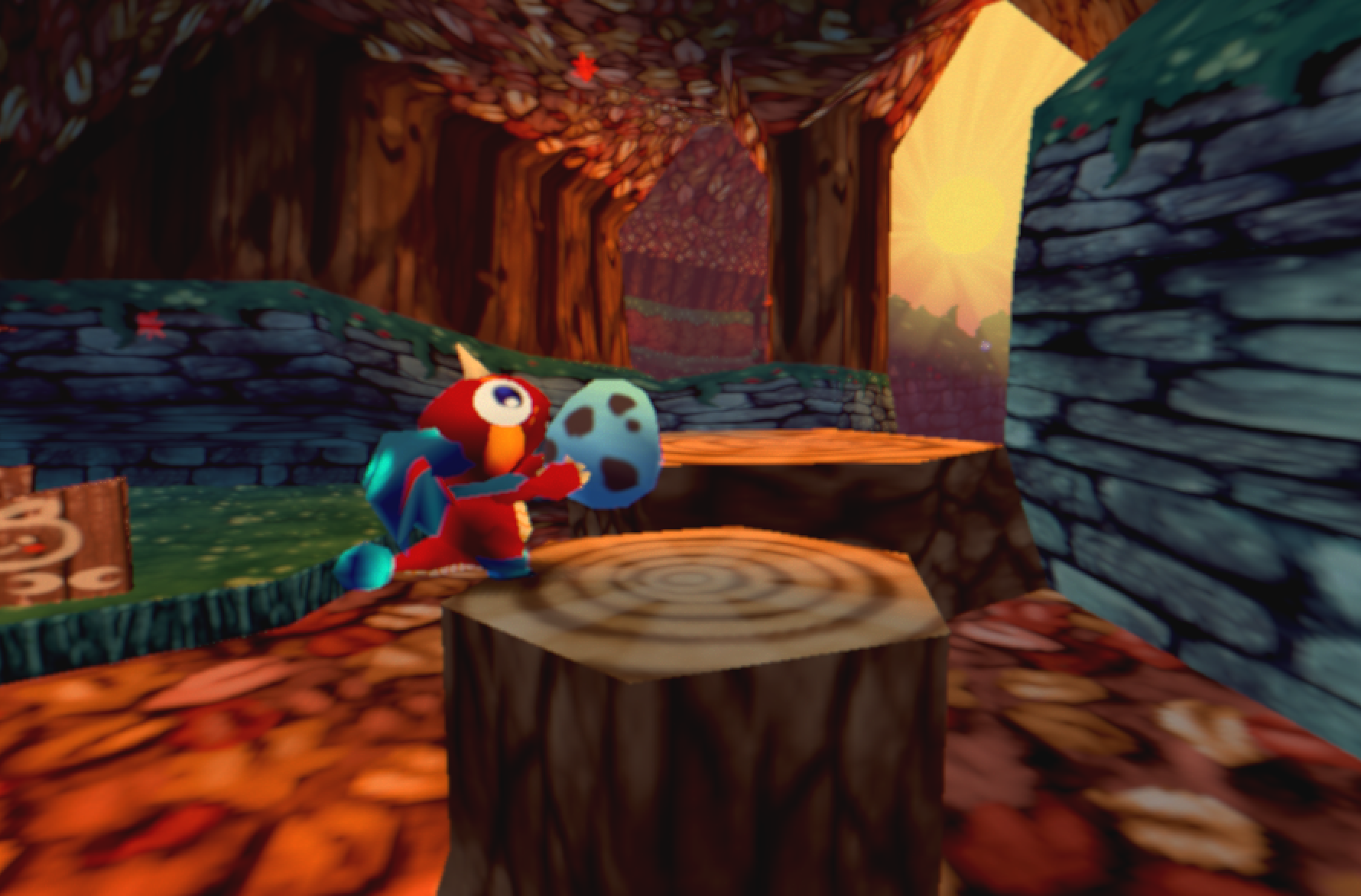

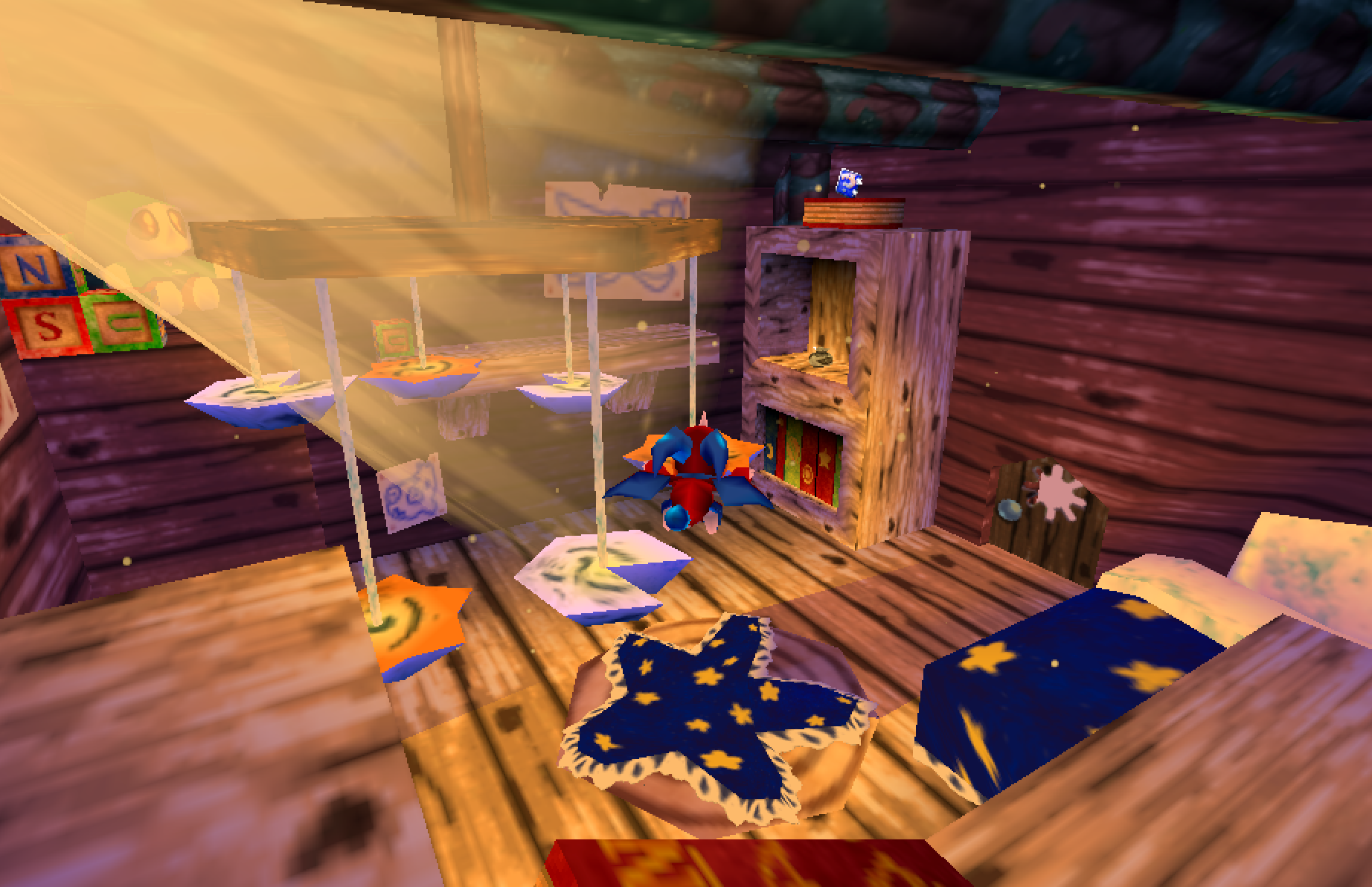

Lately, however, there has been a growing trend of embracing the no less beloved 32-bit and 64-bit history of video games, with nostalgia-infused platformers leading the indie charge, as per usual. Cavern of Dreams, mostly developed by Tyler McMaster, with assistance from composer Benjamin Keckley, voice actor Tasch Ritter and support from Super Rare Games, is one of those attempts to remind the world just what made that era of games so good, as well as stand out as a brilliant adventure in its own right.

The game stars Fynn the Dragon (no relation to Spyro), who’s on an adventure to save their as-yet unhatched siblings from evil. In practice, that mostly involves taking part in platforming and puzzle challenges, unlocking new abilities, and dealing with a cast of interesting characters in varied locations. Or to put it simply, the perfect set up for a video game adventure that is exactly our speed right now.

PUSHING IT TO THE LIMIT

As you might’ve guessed just from looking at it, Cavern of Dreams started out as an exercise in recapturing McMaster’s childhood feelings spent in a bygone era of video games, in which he owned a Nintendo 64.

“I wanted to create a 3D adventure-platformer that captures the experience I had playing N64 games as a kid! I’ve made many games before in a variety of genres,” explains McMaster. “They were all hosted on my itch.io account. This is just my first Steam game! I’ve also been making art, mostly of monster designs, for a long time on Tumblr.”

“Having grown up with the console, I loved how exploration felt in those games. As the years went on, fewer and fewer games captured that same feeling for me, so I wanted to fill that void,” continues McMaster, with enthusiasm. “I believe there is a strength to games made with such drastic limitations, and that those limitations are what facilitate those magical feelings of adventure in the first place. Low fidelity graphics means you have to use your imagination. Small environments means every part of them is important and worth checking out.

“I didn’t have the PlayStation 1 or Sega Saturn consoles growing up, so I don’t have the same familiarity with the benefits of their styles. It’s important to work with what you know, I feel.”

There were several important elements that needed to be achieved in order for Cavern of Dreams to accurately capture the distinct look for the Nintendo 64 then, despite the game coming to PC, rather than the now dated console hardware.

“I needed to make sure the game had bright, rich colors,” explains McMaster. “Specifically, using vertex coloring rather than real time lighting, although it would be cool to see both combined. I also wanted small, densely packed environments that use textures, instead of geometry for details. That and lots of sparkly particles. N64 games loved sparkles.

“The N64 also used a lot of low-fidelity assets like small textures, and simpler models made up of detached parts,” McMaster continues. “How much you’d lean into that is a matter of taste, of course.”

DESIGN CHALLENGES

A large focus of any exploration-driven 3D platformer is often spent on making sure the sandbox levels themselves are fun to get around, and that they have lots of things in them that people actually want to do. For McMaster, that meant a lot of playtesting and iteration – by both himself and other people.

“Fynn’s movement was very important to me and I spent a lot of time refining it,” says McMaster. “I’m still not totally satisfied with how it turned out, but I think the physics of the rolling move and how it cooperates with the rest of the moves that you unlock is still enjoyable. The game’s levels went through many iterations as well; I think for a sandbox-style 3D platformer like this, having levels that invisibly guide the player toward the points of interest and collectibles is paramount, as otherwise players will quickly get frustrated or lost. The last two worlds, which are bigger, were especially difficult to design for this reason!

“At first I also struggled to find a direction to take the gameplay in – that’s why playtesting was so helpful. I was able to isolate what people enjoyed and what they didn’t.”

As for which retro design elements to bring forward, and which to leave in the past, those choices mostly went back to the feelings in particular that McMaster was trying to evoke.

“I prioritized based on the goals of the game. I wanted the game to feel more low-stakes and puzzle-focused, so health and lives were removed,” explains McMaster.

“I wanted the protagonist to feel kind and caring, so combat was removed in favor of environmental interactions and living entities. But things like discrete warps between levels (as opposed to an open-world format where all the maps are loaded at once) became a way to keep environments focused and distinct, so I kept them in.”

When it comes to the other media that inspired work on Cavern of Dreams, some of it is the Rare, Nintendo and Sega suspects that you’d probably have expected, and then some other choices from further afield and outside of games altogether.

“Banjo-Kazooie, Banjo-Tooie, Super Mario 64, Ocarina of Time, and Sonic Adventure 2 were the main influences for Cavern of Dreams in terms of games, with the first two contributing the most in terms of game and level design,” says McMaster. “I also took some inspiration from Breath of the Wild’s Divine Beasts for one level, while Fynn’s rolling was inspired by Super Mario Odyssey.”

“I also took inspiration from medieval bestiaries for character design, and medieval astrology for theming levels and areas, to give the game a historical and fantastical vibe.”

In Cavern of Dreams, you can approach many of the problems presented to you in multiple ways, depending on your skills at the time. That sort of freedom is something of a hallmark of the best platforming and action adventure games of all time, including almost all of Cavern of Dreams’ inspirations, so it is frankly no surprise that this sort of design philosophy made it into the game too.

“Once the movement became more momentum-based, I found I could reach the goals in unintended ways, and that felt very satisfying to me,” explains McMaster. “I like being able to ‘outwit the design’ in other games, and I wanted players to have a similar experience. I also felt that this approach would work better with open-ended levels, where there are multiple directions to arrive at a challenge from.”

Of course, that design choice would mean that the developer would have to put himself into other peoples shoes, and regularly try to look at the game from perspectives outside of his own familiarity with his game world.

“It’s important to think carefully about the psychology of a new player,” says McMaster. “When they are given freedom, what choices will they make? How will the results of those choices teach them how to play in the future? The more open-ended your game is, the more important these questions are. “

LESSONS LEARNED

One of the biggest challenges of making Cavern of Dreams was just how exhausting and demotivating that working on a project in secrecy for a long time can be.

“I burned out hard at several points,” winces McMaster. “I woke up thinking about the game and went to sleep thinking about it, but I couldn’t bring myself to work on it, since it felt like every decision would have dire consequences. It was very painful. The simple solution was just to take actual breaks, to separate myself from the work and go do and experience other things. It’s very important to separate your work and personal life.”

When it comes to what McMaster has learned from his time spent developing his first Steam release, and what he would tell another game developer that was just about to start out on the same journey, the answer is – a lot.

“It’s important to have fun making things,” muses McMaster. “Let yourself make lots of mistakes, as mistakes are how you learn. If you’re always super comfortable when creating, then you should try to push yourself.

“You don’t have to show your work to anyone if you don’t feel it’ll help you, and you especially don’t have to post it online. You’re competing with a galaxy of other content for people’s attention, frequently distributed by algorithms rather than people, so it often won’t be ‘successful’ in a numeric sense. Of course it’s important to market and all that, especially if you’re planning to sell something, but before you worry about marketing, worry about whether you enjoy making games enough to finish one in the first place.

“In the same vein, I think people put too much stock in the performance of others online,” McMaster continues. “People post their best work, of course, but behind every great GIF showcasing a cool prototype, are 99 other attempts that went nowhere. Meanwhile, you get to see every failure you make.

“You should be creating games that excite you specifically, full of things that you care about. That’ll be more productive than asking other people what you should make. Of course you need to think about your target audience, but if you don’t include things you care about, it’ll be harder to find direction and motivation.

“Also, learn from things that aren’t games,” adds McMaster, wisely. “Experience other kinds of art. Art that you aren’t used to. Art that excites or challenges you in some way. You can only create from what you know, after all. Learn from reality, too. If you’re making a racing game, try studying the mechanics of how an engine works, or look at the history of transportation. You just might find a crazy mechanic or design concept that feels fresh.”

VARIETY AND KEEPING IT SIMPLE

As for why people decide to make these retro-style games in the first place, McMaster has a hunch.

“Honestly, I think it’s just a matter of variety,” says McMaster. “There are more games coming out than ever, but so many of those games are derivatives of the same few genres, when the back catalog of gaming history has so many interesting and novel concepts to explore! I feel that the short, random loop of the roguelike is really just people yearning for the arcade genre, for example. Where are the Pacman-likes? How about Chulip-likes?

“The same is true for graphical styles. Game artists of the past spent decades honing appeal in pixel art, low-poly models, and other low-fidelity assets, so modern indie developers with limited time and resources should look to them for inspiration. There’s a lot to learn from.”

He is also keen to point out that your inspirations and aspirations in indie game development don’t necessarily have to be retro, though.

“I would not particularly suggest that people make a retro-style game to learn the ins and outs of game design,” explains McMaster. “I would just tell them to keep it simple, regardless of the genre they’re aiming for. It’s much better to finish a small project than get halfway through a needlessly bloated one and give up because you didn’t plan it properly or couldn’t figure out enough of it.

Cavern of Dreams has been out for a few months now, meaning that its developer has had plenty of time to take in the reactions since launch.

“I can tell the game doesn’t appeal to everyone’s tastes, as the game leans pretty hard into puzzle-solving,” muses McMaster. “I’ve seen some valid criticisms too, which I appreciate. Still, it’s nice when people tell me that they like some specific part of Cavern of Dreams that I made a point to focus on. That makes the whole ordeal feel worthwhile.”

MCV/DEVELOP News, events, research and jobs from the games industry

MCV/DEVELOP News, events, research and jobs from the games industry